History

Tuolumne County Schools

History Lesson

Adapted from the work of former County Assistant Superintendent, Dwain McDonald

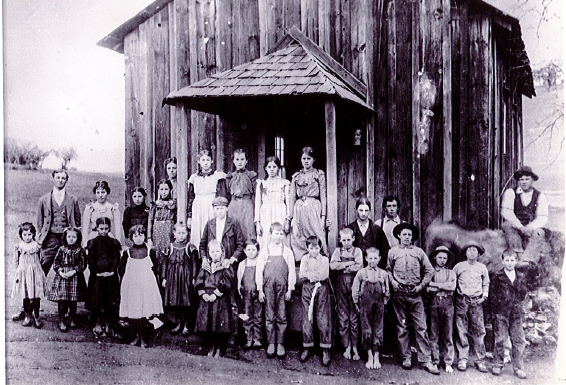

Tuolumne County has a much longer public school history than most regions in California. Schools have been in existence in Tuolumne County since 1852. It was not until the second legislative session of the California State legislature that state funds were appropriated for public schools in California. Tuolumne County received the first support for public schools in 1855. The schools were Sonora, Columbia, Shaw’s Flat, Springfield, Jamestown, Jacksonville, Don Pedro’s Bar, and Chinese Camp.

Local solid community identity has long influenced the various public schools within our county. This fact is evident today because the electorate has enjoyed having a locally elected board of trustees governing the local school district.

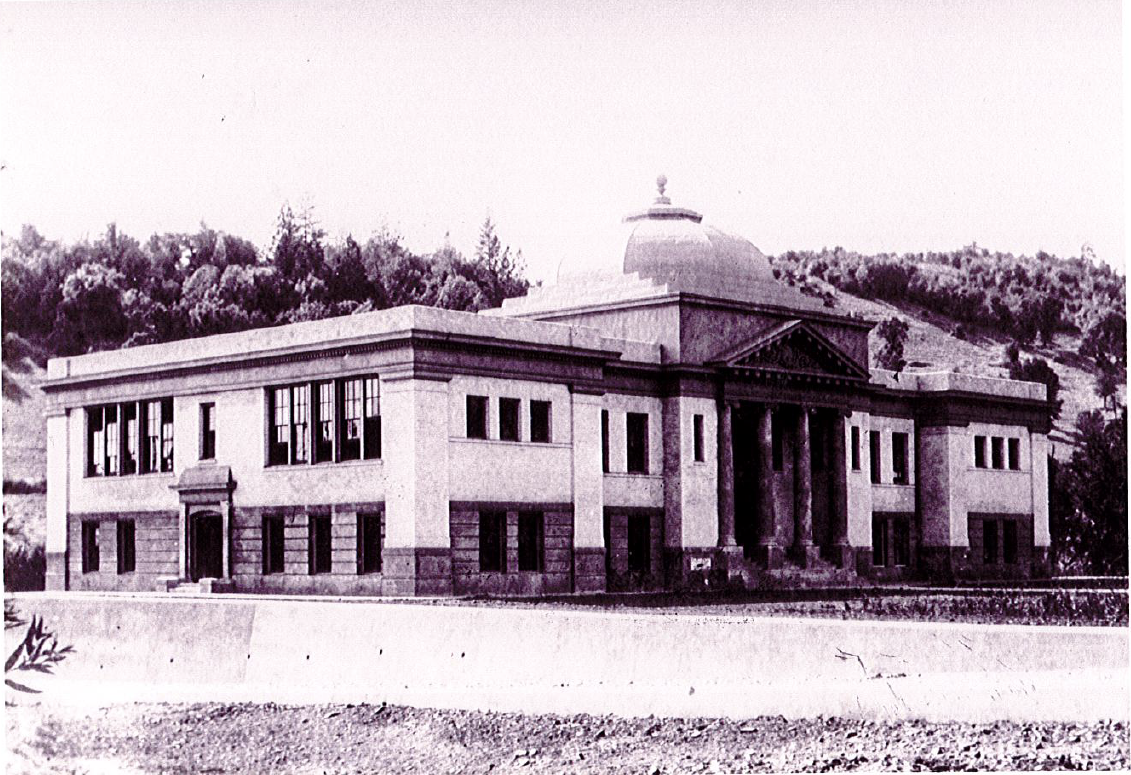

In 1855 there were 809 students between the ages of 4 and 18. That’s the way students were reported to generate school funds. Students did not need to attend school; the state only wanted to know how many resided in the school community. More than forty different public school entities have been in our county’s history. As population centers were established and later diminished, schools were established or reduced accordingly. In the mid 19th century, the only public schools enrolled all-comers, whether 4 or 24 years of age. It was the dream of the county superintendent at that time, Mr. George Morgan, to establish a “high school” by the turn of the century. Finally, in 1902 the Tuolumne County High School was established and held its first classes in the basement floor of the old courthouse in Sonora, with about 15 students attending. Some students lived in Tuolumne and typically came to school by local train service. Within five years, some parents and students thought the trip to Sonora was too arduous and lengthy.

Consequently, a group formed that lobbied for a high school established in Tuolumne. So, in 1911, on the second floor of a commercial building in downtown Tuolumne, the first class met with fewer than a dozen students. Interestingly, 79 years later, a new high school was opened south of Tuolumne River in the Big Oak Flat-Groveland Unified School District for many of the same reasons.

School districts in the county have come to exist to meet particular needs of parents and students at specific times in our history. Over the years, the State of California has drastically changed how schools are created, funded, and managed. Public perceptions of the purposes of schools have significantly changed over the years. For example, for 75 years, no one ever imagined that school transportation was anything but a family responsibility.

Over the years, and probably for years to come, school districts in our county will continue to change to meet the unique needs of each community within our county. For example, a school district such as Columbia Union is the product of many existing and now non-existent places – American Camp, Bear Gulch, Columbia, Deer Creek, Gold Springs, Jupiter, Knickerbocker Flat, Rawhide, Shaws Flat, Springfield, and Tuttletown to name some. The themes that seem to be the genesis of school formation have been:

- Needs of parents to educate their children.

- Ease of attendance for children and families.

- Control of each school by a very locally elected school board.

- Quality of the instructional program.

- Cost and source of funds to conduct the program.

- Value of expenditure per pupil.

- The relative importance of attending one school vs. another.

- Qualities of the physical plant.

Throughout the county today, there are eleven school districts: Sonora Union High with feeder districts Sonora, Columbia, Jamestown, Curtis Creek, Soulsbyville, and Belleview; Summerville Union High with feeder districts Summerville and Twain Harte; and Big Oak Flat-Groveland Unified.

Tuolumne County’s

Superintendents

* Rose R. Morgan was the first woman County Superintendent of Schools in Tuolumne County. Her brother, G.P. Morgan held the office longer (55 years) than any other Superintendent in the United States.

** Richard A. Miller died in an airplane crash while in office.

Chronology of the Office of the County Superintendent &

County Boards of Education in California

Position of County Superintendent of Schools first established in Article IX of California Constitution as ex officio duty of the county assessor.

Office of County Superintendent of Schools recreated (Common School Act).

Legislature creates county boards of examination (headed by county superintendents).

The Legislature authorizes, but repeals in 1874, that a person eligible for city or county superintendent must be a professional teacher and holder of a teacher’s certificate.

It was not until 1947 that professional requirements were required for county superintendents.

New California Constitution established position of County Superintendent of Schools as elected constitutional office.

Legislature created county boards of education (county superintendent and four educators appointed by the county board of supervisors).

Responsibility for child welfare and attendance supervision.

Responsibility for health and physical education.

School finance law establishes three funds to support duties.

Legislature authorizes by law the following:

- The county board of supervisors is permitted to contract with the county superintendent of schools in order to provide health supervision of elementary school buildings and pupils enrolled in any elementary school within the county, carried out by health officers or other employees of the county health department.

- County superintendents are given the discretion to provide for the education of physically handicapped minors who would otherwise be denied proper educational services.

- County superintendents are permitted, with the approval of the county boards of education, to provide for the preparation and coordination of courses of study, and for conducting and coordinating research and guidance activities for elementary and high schools under their jurisdiction.

Additional powers granted by statute, including mandates to serve small school districts.

Constitutional amendment authorized legislature to prescribe qualifications and fix salaries of county superintendents.

County school service fund is created, increasing powers and duties of county superintendent.

The Legislature enacts a law establishing elected county boards of education, consisting of five or seven members to be elected at large, and at least one member residing in each of the designated trustee areas determined by the county committee on school district reorganization.

Constitutional amendment authorized county voters in non-chartered to choose between an elected or appointed county superintendent, and authorizes the county board of education to fix the salary of the county superintendent.

Assembly Bill 1200 (Chapter 1213, Statutes of 1991), which took effect on January 1, 1992, redefined and expanded county superintendents’ fiscal oversight of school districts responsibilities.

Assembly Bill 2756 (Chapter 52, Statutes of 2004), which took effect on June 21, 2004, made significant changes to the school district financial accountability statutes.

Eliezer Williams, et al., v. State of California, et al. (“Williams”) settled resulting in legislative enactments which required county superintendents to conduct annual visits of underperforming schools to review the sufficiency of instructional materials, adequacy of school facilities, and verify information on the school accountability report card. County superintendents also required to submit annual reports of such visits to district governing boards, county boards of education, and county boards of supervisors.

The Quality Education Investment Act (Ed. Code §§ 52055.700, et seq.) was enacted for the purpose of, among other things, implementing the settlement in CTA, et al. v. Schwarzenegger, et al. The legislation required county superintendents to annually monitor implementation QEIA in funded schools.

Valenzuela v. O’Connell, et al. (“Valenzuela”), a lawsuit challenging the California High School Exit Exam (“CAHSEE”), settled resulting in legislative enactments which required county superintendents to conduct oversight activities including (1) verifying that eligible pupils are informed that they are entitled to receive intensive instruction and services for up to two consecutive academic years after completion of grade 12 or until the pupil has passed both parts of the CAHSEE, and (2) ensuring that pupils who elect to receive services are being served.

Assembly Bill 97 (Chapter 47, Statutes of 2013), amended by Senate Bill 97 (Chapter 357, Statutes of 2013), introduced the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) to reform California’s educational funding system. The LCFF instituted a change in local educational agency accountability for unrestricted funding in the form of three-year LCAPs, with annual updates that focus on service outcomes for all students. (Ed. Code § 52060, et seq.) It requires county superintendents to review and approve or deny their local districts’ LCAPs concurrently with the county superintendents’ review of their local districts’ budgets and to provide technical assistance when an LCAP is denied. This builds upon county superintendents’ existing oversight functions under Assembly Bill 1200 and Williams.